Why Fly Presentation Matters

Most of the time, but not always, trout only eat things that look natural to them.

When we talk about presentation, we’re talking about the most crucial element of fly fishing. How does the fly look to a trout in the instant before it decides to eat, or not?

Granted, with brains the sizes of marbles, trout aren’t terribly deep thinkers. But they are critics to the extent that instinct tells them what looks natural and what does not.

Most of the time, but not always, trout only eat things that look natural to them, especially in the fly-fishing arena.

My best anecdote that puts the whole fly presentation issue into perspective is a saltwater fishing story. I was working the flats with Bill Curtis, a legend among south Florida fly guides, and we saw a big permit cruise into the shallows. I have no idea how big the fish really was; suffice to say it looked like a metal trash can lid shimmering under the surface.

I made what I thought was a perfect cast, about 60 feet, slightly leading the fish, with the fly landing about five feet past the permit. I made a few strips of the line, to skip my crab fly along the bottom into what I thought would be the feeding zone. The permit finned away, more annoyed than spooked.

“What went wrong?” I asked. “I made a great cast and didn’t line the fish…”

Bill picked up his push pole and grumbled down at me on the deck, “Fish aren’t used to their food attacking them.”

Good point.

Apply that thinking to all your fly fishing, especially trout fishing. An insect–be it a nymph floating under the surface or a dun drying its wings on the surface–is usually moving at the mercy of the current. An emerging insect is swimming toward the surface. A baitfish that senses a predatory trout in its vicinity will swim nervously away from the fish.

These subtleties are remarkably important.

So, the trick with presentation is to make flies act how they’re designed to look: dead drift nymphs with the current, with no drag; make spinners fall from the sky and lie almost lifeless on the surface; swim your streamers away from cover and obstructions.

Certainly, there are times when the rules can be bent: twitch a grasshopper near a cutbank, dead-drift a Woolly Bugger through a deep run, fish dry flies wet, fish wet flies dry, and so on. But by and large, if you present your flies in a way that makes them behave as naturally as possible, all the while keeping your presence as stealthy and blended into the environment as possible, you’ve discovered the number one secret to fly-fishing success.

Whether you can cast 20 feet or 120 feet, and whether you have a spot-on matching fly pattern or an old generic standard, what happens in the first seconds after the fly hits the water matters most. Always.

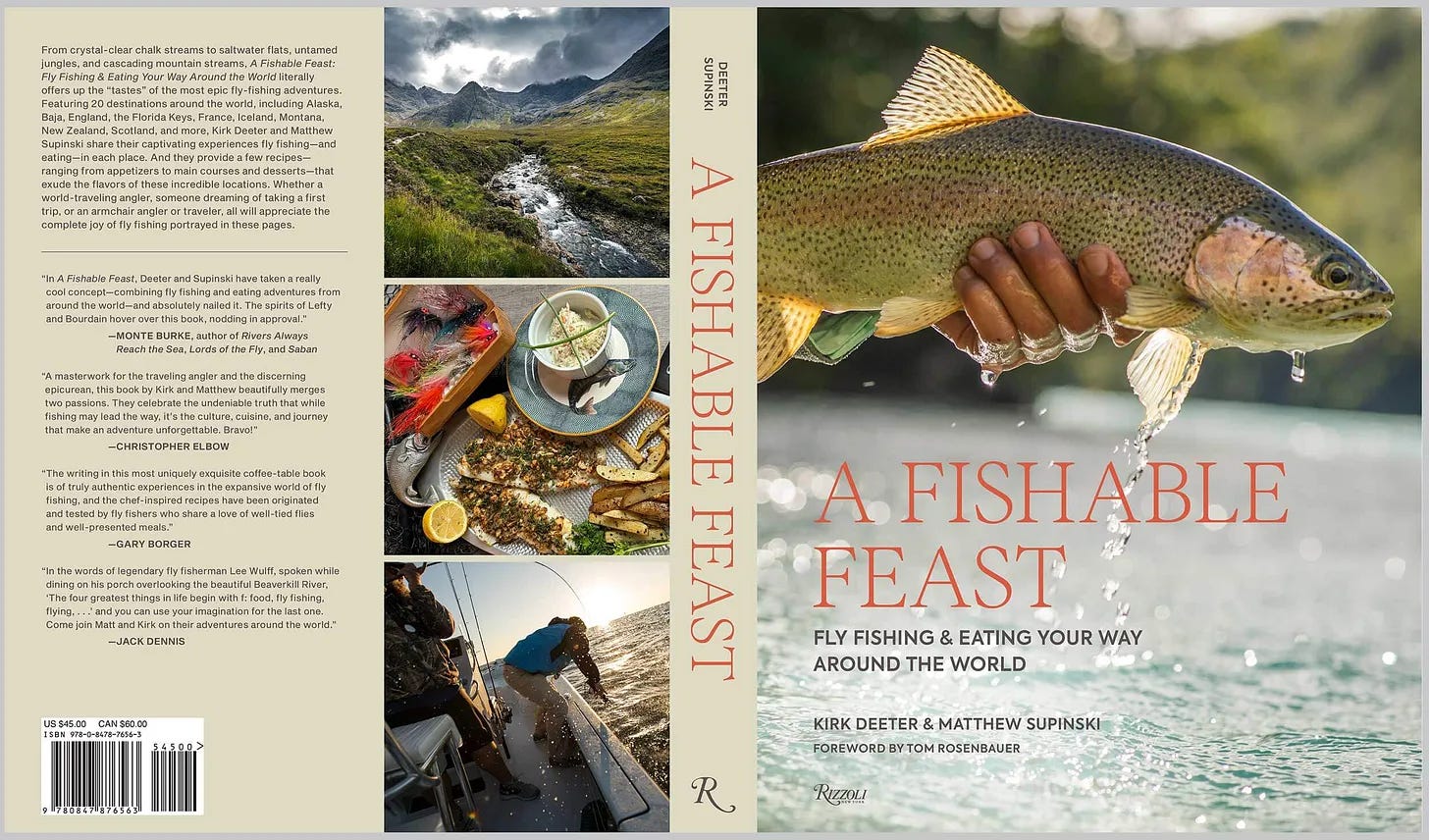

Check out KD’s new book: A Fishable Feast: Fly Fishing and Eating Your Way Around the World—coming out next spring, published by Rizzoli in New York. (Pre-order at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Books-A-Million.)