They Ain’t From Around Here

Let’s be honest about non-native fish.

By Miles Nolte

Fly anglers don’t lack opinions, but our opinions aren’t necessarily coherent, or, you know, logical.

Walt Whitman understood us: “Do I contradict myself? Very well, then I contradict myself. I am large. I contain multitudes.”

Literary though we may be, we’re also kind of annoying (see above quote) and hypocritical, particularly when discussing native and non-native fish. Of late, a caustic plume of unnecessarily divisive sentiment has carved fissures in the mostly well-meaning community of conservation minded fly anglers. This I find both disheartening and counterproductive. As a member of that community who has tried to create and promote media that elevates fish conservation in general and native fish conservation in particular, I think it’s time we admitted some uncomfortable truths.

We’re anglers first and amateur aquatic ecologists second. We support the fish we want to catch in the places we want to catch them. In debates over habitat, resource allocation and fisheries management, we rarely share common perspective. The management and conservation initiatives anglers support are generally dictated by where we live and the species we target.

No matter how much we crow about protecting native fish, most American fishing involves catching fish planted by people, which means that the primary driver pushing anglers to care about aquatic ecosystems also depends on those unnatural fish. Without non-native trout, Trout Unlimited doesn’t exist. Neither does all the habitat restoration work that organization identifies, funds and mobilizes. If bonefish and tarpon weren’t so much damn fun to cast at and pull on, The Bonefish & Tarpon Trust and the relevant studies they support, never happens. We can and do conserve and restore habitats, ecosystems and fisheries, but by and large anglers–you and me–do so to protect and improve our own fishing.

I’m not attacking native fish advocates or their work, and I’m not promoting non-native fish conservation at the expense of the species that evolved in our systems. I’m calling on all of us to lower the tension and the holier-than-thou-ism a few degrees by remembering that we all have common motivations and common interests. We’re far better off harnessing those commonalities than seeking opportunities for judgement and infighting.

The North American Model of Conservation hinges on revenue from anglers (and hunters). We spend our money on licenses, gear and donations because we love fishing, not fish. Non-anglers don’t get fish tattoos or scatter their homes in fish décor, and they don’t spend huge amounts of money or volunteer their time to protect or rehabilitate fisheries and habitat. The people who do the most for fish are the people who like to catch them, and we are motivated by the fish we hope to catch.

So, let’s admit our desires. We want strong populations of species we target, be they native or not. We also like the idea of protecting the native species we don’t target (Yeah, healthy ecosystems!), but that is far from the primary motivator.

Big brown trout sway at the surface of our sport, the pinnacle target for American fly anglers (and probably most fly anglers worldwide). A quick skim through Instagram confirms the towering pedestal on which we place Salmo trutta. Of course, browns are as native to American waters as snakeheads, centrepinning, Tenkara, or Euro nymphing. (Before you East Coast, tight line trout hard cores start yelling, yes, I know about Joe Humphries; but Euro nymphing is still Euro.)

Rainbows are equally alien in most of the places they currently swim, and yet they (along with stocked browns) anchor one of America’s strongest and most accessible fishing cultures: truck trout. Our most popular freshwater fish, largemouth bass, are native but weren’t ubiquitous until they got dumped into every newly created reservoir and farm pond after WWII. Don’t assume the walleye in your local lake are endemic either, because they’re probably not. Stripers are a distinctly right coast species, or they were until we sent them to California on railcars, where they’re now a conservation target. Are Pacific salmon invaders to Lake Michigan? Damn right, but they’re also the reason sport fishing, and angler supported fishing conservation, exists in the Great Lakes. Once upon a time (say 20 years ago) Cyprinus carpio smelled like an invasive species just about all anglers could agree to hate. Today, all the cool kids fly fish for carp.

Sometimes our feelings about a non-native fish pivot 180 degrees in different parts of the same watershed. Rainbow trout are reviled in the South Fork of the Snake but revered in the Henry’s Fork of the Snake. At first glance, that may seem disingenuous or even contradictory, but I would argue it’s a perfect example of how we should approach contemporary fisheries management. It’s logically coherent in a messed up, post-modern kind of way. Those may be the same river but they’re completely different fisheries, which demonstrates the level of nuance we need to bring to discussions about fish populations in the 21st century Anthropocene.

On the Henry’s Fork, where cutthroat are all but extirpated with little chance of returning without drastic and painful changes, rainbows are the main attraction. On the South Fork, where cutthroat populations can realistically remain robust and healthy, we should do everything we can to keep the rainbow numbers down.

That nuance is what I find so often lacking on both sides of the native vs. introduced fish debates. Ecosystems and fisheries have changed, and the way we approach conservation needs to catch up.

Demanding an absolutist position on native flora and fauna sounds laudable, utopic even, until you start to unravel the reality of our situation. American waterways do not resemble their “native” state. I challenge anyone to find a stream, river, pond, lake, or ocean in or adjacent to the lower 48 states that hasn’t been altered by humanity in the past 400 years or so. We cannot bring our waterways back to the before times, and even if we could, it wouldn’t matter. The people aren’t going anywhere–we’re still doing what we do, interfering with and taking advantage of the places where we live.

We cannot and should not limit conversations and efforts to native-only aquatic ecosystem restoration. Doing so will doom our fisheries and our fishing. First, it’s just not realistic. Recall the Second Law of Thermodynamics: entropy increases over time. In other words, things fall apart; they don’t fall back together. Second, that approach threatens to undermine our advocacy power. If we tell anglers they have to support all native or nothing, we risk losing support. We want more of us to get involved in meaningful conservation. The unfortunate reality of that means recognizing that both native and non-native fish are important to us, so long as they’re fun to catch.

Another truth I think we need to admit, the whole “natives only” attitude is not just disingenuous, it reinforces our already problematic bent toward elitism. Non-native fish are accessible to many people, especially (gasp!) stocked fish. To refresh a point I raised earlier, trout fishing culture (and therefore, fly-fishing culture) in the United States depends on hatchery raised non-natives. Stocked, non-native trout anchor a significant part of the bedrock of modern American fishing culture. Does that mean we should dump hatchery mutants in every river, stream, lake, or pond where people want to fish for them? Of course not. The data are clear about the damage that hatchery fish can and do wreak on native fishes, especially anadromous species. But stocker streams are critical for angler recruitment and retention. People want to fish for trout, and not everyone has the luxury of traveling to do so.

Would our local fisheries be better off if everyone boycotted planted fish and concentrated on natives instead? Maybe. Maybe not. I love catching panfish, suckers, gar, pickerel and bowfin on flies, but I’d be concerned about the repercussions if everyone who goes after trout now shifted their impacts to those species. The whole argument is purely a navel-gazing thought-experiment, however, because I don’t see that happening. At least not until climate change eradicates the cold water fisheries we have left.

I’m imagining some of you screaming right now, “Why are you bashing native fish conservation? What’s wrong with you? We’re finally getting anglers to talk a little bit about the importance of native fish and you’re mocking that effort?” And to you I say, hold on. We probably agree more than you realize. I’m making a broader point. Bear with me.

On the other side of the native vs. planted debate, the past 150 years of fisheries management have unfairly and unnecessarily privileged planting non-native fish for angler amusement. The colonizing impulse that spread Europeans all over the globe forever altered both the terrestrial and aquatic habitats of what we now call America. Our founding fathers treated native species in much the same way as native peoples. And, just as I think any reasonable person can agree European arrival in the New World didn’t work out well for Native Americans, neither has it benefitted native fishes. Manifest Destiny cast the landscape as an incomplete canvas to which humanity is called to add color and form. Godly intentions or not, that hubris didn’t restore Eden, quite the opposite.

The Eurocentric philosophy of fisheries management has evolved, but too often still tilts toward maximizing consumptive recreation opportunities, even at the expense of sensitive or native populations. That approach does not benefit our ecosystems, our fisheries, our fishing experiences, or the longevity of our favorite thing to do. I’m not advocating that we relapse into the ignorant myopia of hatcheries as saviors and bucket biologists as missionaries. But, we also should not claim born again religious conversion and expect our community to adhere to native-only evangelical fealty.

Over the past decade or so, I’ve noticed a profound and mostly positive rhetorical shift. We’re talking about native fish in ways we never have before, and our language shapes more than just the texture of our discussions. For example, Minnesota’s recent “No Junk Fish” legislation, which recognizes the value and significance of previously maligned native fishes and creates meaningful funding and infrastructure to better understand their populations and effectively monitor and manage them. That, my friends, represents real progress, and we need more of it.

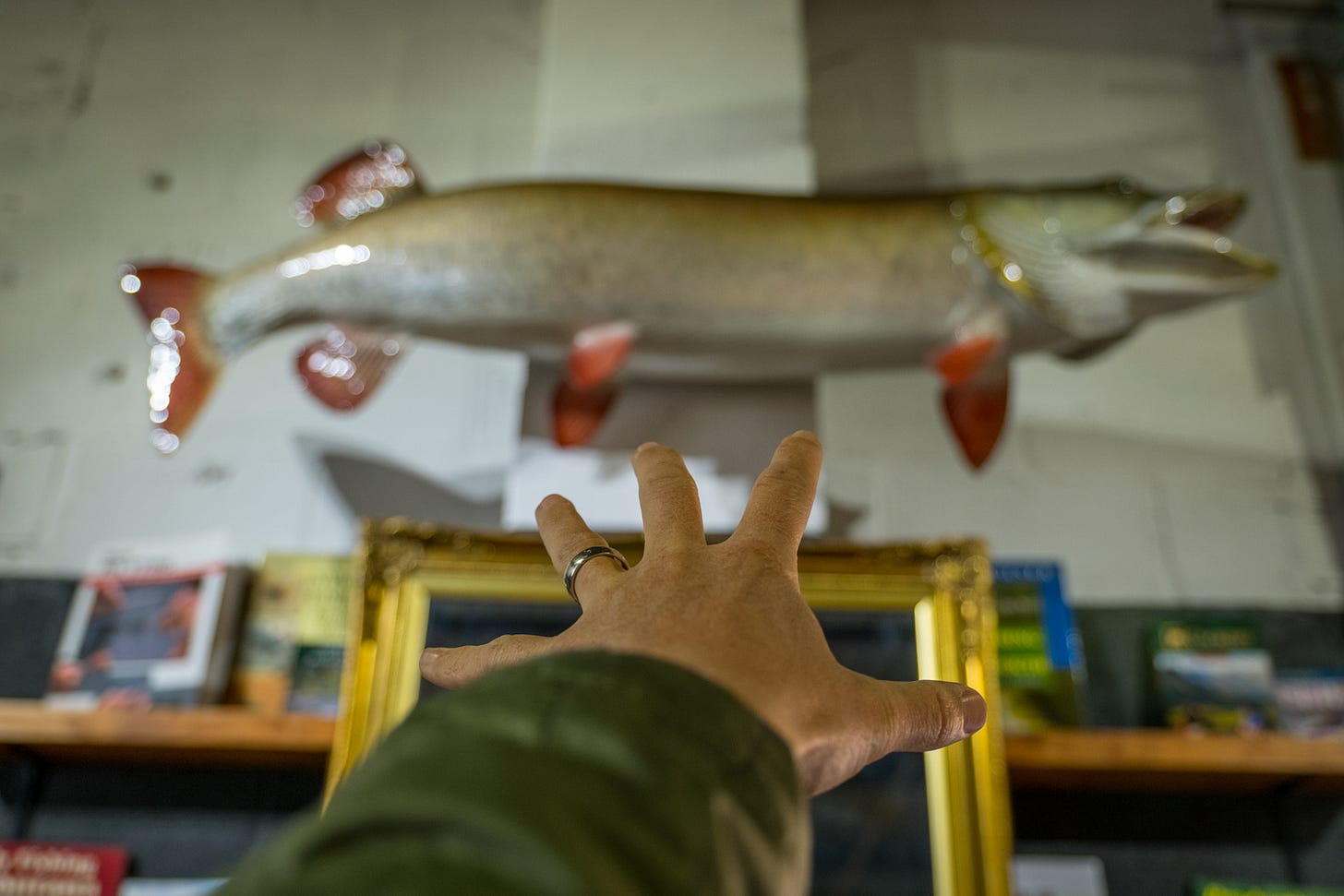

We’ve also successfully re-branded cutthroat from enjoyable afterthought to primary target in certain parts of the Mountain West (not so much whitefish, though). Smallmouth and musky seem to get more popular by the week, and the more people who come to love these fish through catching them (or at least trying, in the case of musky), the more people we can call on as allies when watersheds are threatened. Anglers are finally starting to discover the unrealized joy swimming all around them in the form of previously ignored native fish. Everyone reading this should try to catch a bigmouth buffalo (a native, fickle, hard fighting sucker species that eats dry flies and nymphs). You can thank me later.

But when the howling winds of public opinion echo only idealistic extremes, moderate rational perspectives get silenced and then alienated. When we signal to our community that they’re no longer allowed to profess affinity for non-native species or advocate conservation efforts that focus on those fishes, we insult our friends and de-incentivize conservation efforts for all fisheries.

Additionally, if fly anglers stray too far toward native-only punditry, we stuff ourselves into a box of hypocrisy. Publicly, we advocate for native fish. Privately, we spend most of our time fishing for aliens. We cannot (and absolutely should not) demand that anglers choose a side. Let’s get away from this unhelpful and unrealistic binary. You can love rainbow trout and support conservation efforts for fine-spotted cutthroat on the Snake River, if you’re willing to embrace the cognitive dissonance of contemporary ecological messiness.

Let’s all slide off our extremely tall ponies and take a moment of honest, personal reflection. Fly fishing, like any other kind of fishing, is a blood sport, even if you don’t kill any fish. We harm fish because doing so brings us pleasure. We primarily care about fish because we enjoy messing with them in ways that are detrimental to their fitness, health and survival. Second, we are not native fish saviors. At least, that’s not our core motivation. We like the fish we fish for, and we justify our support for those fish. If you happen to chase cutthroat, or tarpon, or smallmouth in their historic habitat, good for you. You get to dress yourself as a native fish advocate, but chances are you’re an angler first.

You didn’t fall in love with catching bluegills at six-years-old because they are endemic. You fell in love with catching bluegills because it was fun (and still is). When a permit inhales your fly, your first thought isn’t, “Oh my god, what a gorgeous native fish,” it’s, “Holy shit, he ate it!”

My point is, you’re already kind of a bad person, and so am I. We torture creatures that are smaller than us and dumber than us for fun. We drive cars, live in houses, fly on planes and engage daily in activities that harm this planet’s ecosystems directly and indirectly. Let’s stop pretending we stand atop a moral mountain surveying other people’s carnage. Some of us are committed conservationists who work our asses off to improve and maintain fresh and saltwater ecosystems, but the motivation for that work isn’t entirely altruistic.

Our fish advocacy sprouts from fishing–what we want to catch dictates our interests and efforts. Admitting that allows us to be intellectually honest. (Doesn’t that feel better?) We don’t need some kind of native fish purity test; we need to admit, recognize and harness the core of collective angler advocacy: fish that are fun to catch. If you think that’s wrong, you should probably stop fishing. Sell your rods, tackle, flies and tying supplies and donate the proceeds to a fish conservation organization that’s not aligned with fishing. I’d offer a recommendation, but I don’t know any.

As fly anglers, we have an annoying habit of claiming superiority: in our angling preferences, our literary sensibilities, our diction (see: the majority of this essay including the word “diction”), our beverage choices (real fly purists only drink sours and hazy IPAs these days) and our opinions about fisheries management. That hubris is, at best, obnoxious and, at worst, self-destructive. When it comes to protecting our beloved fish populations–native and non–and the habitat they need to survive, we are better off working toward consensus than allowing infighting or perceived moral high-ground to dilute our collective power.

We clearly can’t agree on much, but if we can agree that fish conservation is both messy and selfish, then we open up a space for all of us to get involved. Clinging to a security blanket of simplicity doesn’t serve us. If we wanted things to be simple, we’d save ourselves a lot of time and headache and just use bait.

Miles Nolte has worked as a magazine columnist, writing instructor, freelance writer and digital editor. Currently, he is the Director of Brand Marketing at Skwala Fishing.

One of the better fishing pieces I’ve read in a good long while. And you very eloquently preached for all of us to not be so “holier-than-thou” while not sounding too “holier-than-thou” … which is no small feat. I am constantly self conscious about sounding too holier than thou when trying to help other anglers. But this is just well thought out and articulated. Bravo! 👏🏽

Tim, this article is a must read for all fishers. I must admit, I would like to time travel to those years when native fish abounded in our North American waters. But alas, I find myself just trying to catch and release anything moving in the water for the thrill and then for the peaceful feeling of it slipping through my hand into its world. Thanks for the insightful comments. Jim